The Handshake

In the first weeks of my final year of college at the University of Maine in Orono, word came that our campus was going to host a visit by the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy. He would be coming to give an address and to be awarded an honorary degree.

At the time, I was paying my way through college with a job as dormitory director. I had my own apartment on the first floor, and was responsible for supervising the eight floor counselors — two per floor, and about 400 students in residence. That particular semester I was spending each week day as a student teacher in nearby Bangor High School, completing my requirements for teaching certification.

I was also beginning my term as President of the Senior Skulls, a men’s honorary service organization that was often called on, among other things, to serve as hosts for campus visitors. We were given word that our group would serve those traveling with the President, with details to follow.

During the short time leading up to the event, we learned that the President’s travel that day would begin at the Kennedy compound in Hyannis on Cape Cod. He would first travel to Portland, there to be joined by Maine’s Governor and congressional delegation along with a small press corps. The group would fly in three helicopters, first to Campobello Island to visit Roosevelt Park and Cottage. That facility was undergoing restoration, having served as a summer retreat for the Roosevelt’s in the 1920’s and 30’s. The Island itself is actually in New Brunswick, Canada, accessible by bridge from the town of Lubec on Maine’s eastern-most tip of land. It’s 1,000 or so residents could reach their homeland by seasonal ferry service; otherwise, they had to return to the US and drive north to a border crossing.

A fly-over of the Bay of Fundy was to follow, giving the President a view of a recently completed tidal power complex stretching across the Bay and taking advantage of both incoming and outgoing tides to produce electrical power. Following these visits, the helicopters would bring the assemblage to the Orono campus, landing on a practice football field adjacent to the stadium.

With the President’s arrival just days away, I learned I was to serve as host for the White House Physician, Retired Vice Adm. George G. Burkley. My task was to welcome him to the campus and escort him from the helicopter landing area, across the football field, and show him to his assigned seat on the speaker’s platform. Following the President’s address and honorary degree ceremony, I was to escort him back to the helicopter (Dr. Burkeley died in 1991 at age 88).

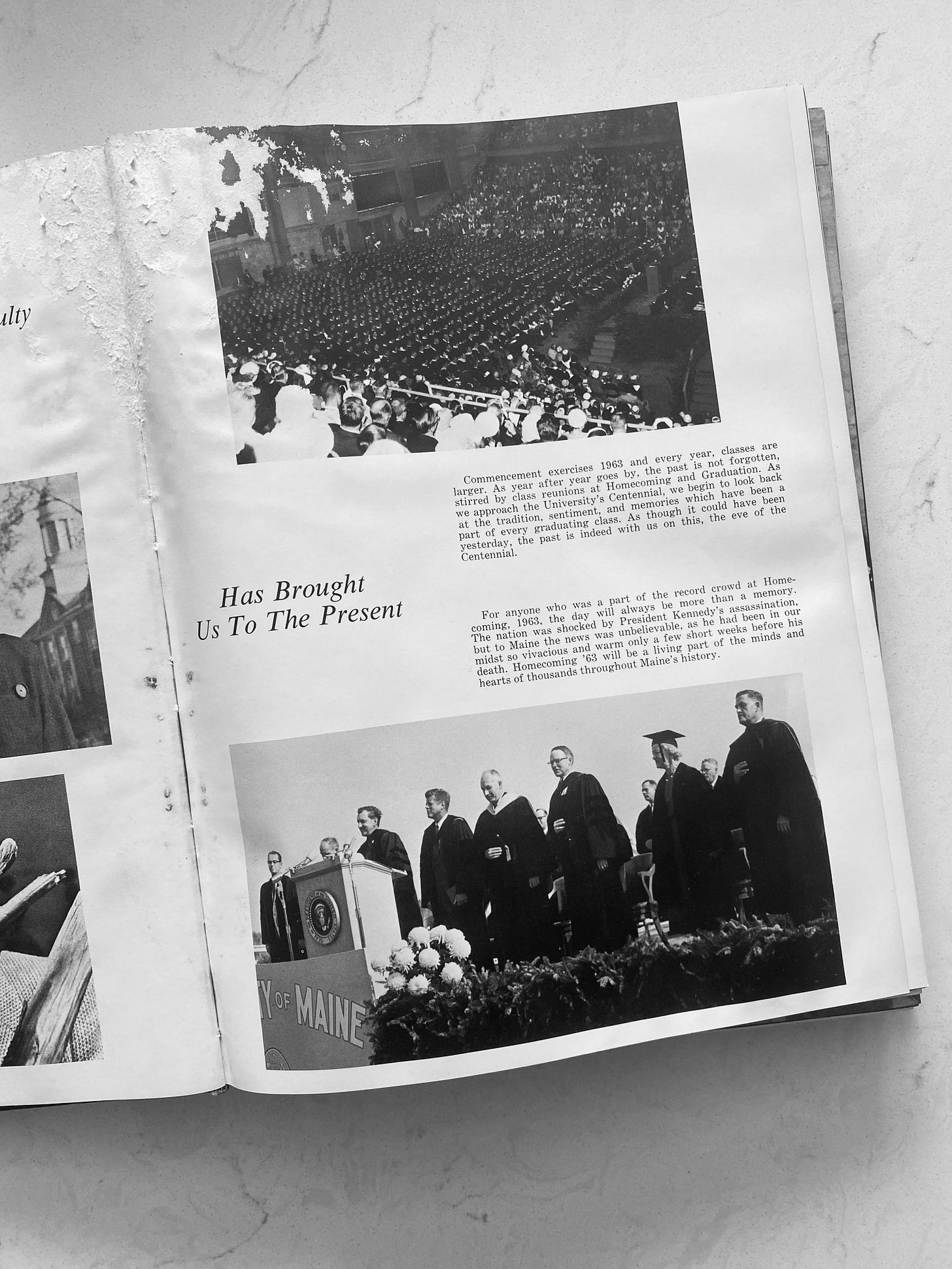

There was great excitement on the day the President arrived, Saturday, the 19th of October, 1963. The three, large, loud and identical aircraft arrived in trail out of a cloudless northern sky and landed and shut down without incident. I introduced myself to Dr. Burkley, we chatted for a few minutes as the rest of the party deplaned, and then he and I walked across the field to the speakers podium. The stands at the stadium were filled with students and members of the public who wanted to see and hear the famous President.

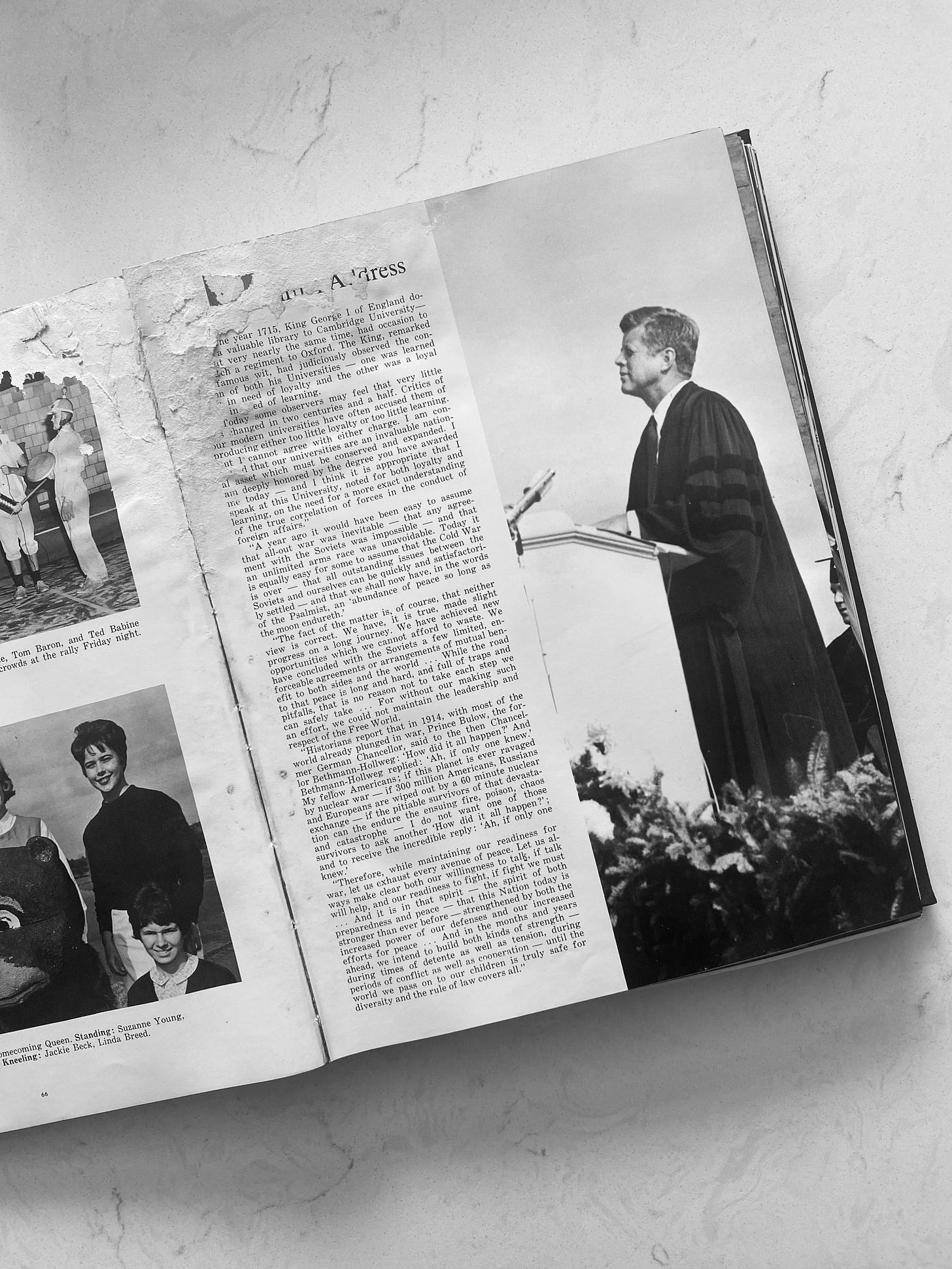

Dr. Lloyd Elliott, University of Maine President, welcomed President Kennedy at the landing site and escorted him to the podium. They were surrounded by a dozen or so Secret Service agents at all times. The President spoke after receiving an honorary degree of doctor of laws. In his opening words he referred to Dr. Lloyd H. Elliott, president of the university, to Governor John H. Reed, and to U.S. Senators Margaret Chase Smith and Edmund S. Muskie, and U.S. Representatives Stanley R. Tupper and Clifford G. McIntire, Maine’s Congressional delegation.

The address was well received. I had listened from the ground next to the podium, where I awaited the re-appearance of Dr. Burkley from his seat on the stage. We met once again, and the two of us returned to the helicopters. He was one of those riding with President Kennedy in the lead aircraft. I said goodby to him and walked a short distance back to the opening between the two fields.

At that point, I looked across the field toward the stands, where I saw both President Kennedy and Dr. Elliott moving slowly along the low, chain-link fence in front of the stands. They were surrounded by the Secret Service agents, and President Kennedy was shaking hands with people from the audience who were lined up on the opposite side. Apparently this was not an uncommon occurrence. This went on for several minutes. I glanced back to the helicopters, noticing that most of his traveling party had already re-boarded and were waiting for the President’s return.

When I turned my attention back to the field, I saw that President Kennedy and Dr. Elliott had moved away from the fence and were proceeding across the field — directly to where I was standing. The Secret Service agents had formed a loose circle around the two men. As I was deciding which way to move — left or right, to allow them passage, one of the agents in the front of the circle reached his arm toward me. I think he was going to politely yet firmly direct me to step aside (which I was already doing). Just then, a hand came from inside the circle, over the agent’s arm, and grabbed my shoulder. It was Dr. Elliott, whom I knew well. He held me in position as he and President Kennedy stopped walking. The agents paused while surrounding the three of us.

Dr. Elliott then introduced me to President John F. Kennedy, explaining briefly who I was and why I was there that day along with my fellow Senior Skulls. The President shook my hand, spoke a few words, and I in return spoke a few words. (Unfortunately, I have no recollection of what exactly was said by either of us). It was all over in a few seconds, and Dr. Elliott, ever the smooth gentleman, suggested it was time to get the President to his helicopter and remain on schedule.

I stood in place as the two men and the circle of agents moved away through the opening and onward toward the aircraft — which now were starting their engines. I remained there until they departed, flew over the campus, and disappeared from sight.

What I couldn’t have known is that two days later, in Dallas, Texas, a young ex-Marine named Lee Harvey Oswald was hired as a part-time worker at the Texas School Book Depository in Dealey Plaza.

Thirty four days later, on Friday November the 22nd, I was in the University’s Planetarium with a busload of my math and science students. We were on a mid-day field trip to the Emera Astronomy Center, enjoying a very well done show illustrating the orbital movement of the planets and our moon. The room was pitch black, and we were watching images of the stellar bodies moving across the domed ceiling while listening to a pre-programmed narrative.

Suddenly, without warning, someone opened a door along an upper wall and a shaft of bright light cut the room in half. Then, whoever was out there yelled: “The President’s been shot!” and shut the door again. What was that all about? What was going on? We, of course, had no idea. It was almost unimaginable.

The light show, on automatic, continued. After several minutes, the clearly rattled students began to quiet down, although they continued to murmur and had clearly lost all interest in the production, as had I. When the show ended, we quickly exited the facility and returned to our school bus. Less than an hour later, we had returned to the high school in Bangor where the class was dismissed for the day.

I immediately returned to campus, although I’m sure I listened to my car radio along the way for more news. Eventually, back in my dormitory, I was able to find a television set and got up to speed with what had happened in Dallas, Texas, on that fateful day. All the while, I kept thinking: what if he dies? I shook that man’s hand just a few weeks ago. And, now he might have been assassinated? It was difficult to imagine such a thing.

I left campus that evening, now knowing that the President was dead, and traveled to my home, where for the next several days the television remained on continuously. There was the swearing in of Lyndon B. Johnson as the new President; the return of Kennedy’s remains to Washington, D.C.; the bloody dress of Mrs. Kennedy; the capture and arrest of Lee Harvey Oswald; the casket on display at the White House and later at the Capitol; the appearance of Oswald in the Police Headquarters and his murder at the hands of Jack Ruby; and of course the funeral and burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

And, then the questions began. How could this have happened? And, in spite of an investigation by the Warren Commission, and several subsequent investigations, and answers supplied, for many the questions continue.

For me, there will always be the memory of that face-to-face meeting, and of the momentary pause and brief handshake on the green field of the football stadium at the University of Maine. For many of us of that era, John F. Kennedy was an inspiration, a man with whom I shared time in a Naval uniform, who established the Peace Corps, and who encouraged us to “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”